Oyster Harvesting Vessels and Tools: A Historical and Technological Evolution

Early Beginnings and Indigenous Influence

The roots of oyster harvesting in North America trace back to the Indigenous peoples who first developed techniques for gathering oysters. Early European settlers quickly adopted these methods, particularly the use of dugout canoes, and adapted them to suit their needs. Indigenous canoes were traditionally crafted from hardwoods like maple and oak, but settlers favored pine due to its greater abundance and ease of working. The introduction of iron tools further refined boat construction, leading to improvements in design. Over time, settlers modified these early craft, resulting in a variety of small boats—such as skiffs, sharpies, and open rowboats—that became essential for oyster harvesting.

“‘Oyster boat’ may refer to anything from a skiff to a steamer. Essentially, it means any boat associated in some way with oystering. More specifically, it functions, solely or jointly, as a platform from which oysters are harvested (raked, tonged, or dredged), as a vehicle for freighting and shifting them, or for maintaining the beds.” (Kochiss 1991, 91)

The Rise of Sail-Powered Craft

By the 19th century, sail-powered vessels, such as catboats and sloops, became the preferred choice for oystermen, thanks to their mobility and capacity. These boats were particularly well-suited for the shallow waters of regions like Long Island’s Great South Bay. The flat-bottomed skiff, which followed the indigenous canoe design, remained popular due to its simplicity and ease of construction. Its flat-bottomed hull allowed it to navigate easily through sandbars and shoals.

Among the boats that emerged, the sharpie, known for its flat-bottomed hull, became especially favored for tonging in shallow, protected waters. However, it was less suited for dredging, making it an ideal, inexpensive, and easy-to-maintain vessel for many oystermen. Meanwhile, larger boats, such as those resembling sloops, offered additional space and stability, which proved perfect for transporting oysters to market.

The Evolution of the New York Sloop

In the latter half of the 19th century, the cat- or sloop-rigged centerboarder became a widespread vessel in the Great South Bay. Originally designed for general work in shallow waters, this boat became integral to the local oyster industry. Known as the New York sloop, it emerged in the 1830s, characterized by its wide, shoal centerboard and V-shaped hull. Adaptable, seaworthy, and perfectly suited for oyster harvesting, the New York sloop quickly spread throughout the northeastern United States, including New Jersey and Long Island Sound.

Typically ranging from 18 to 36 feet in length, New York sloops were highly effective for the needs of oystermen. Many fast oyster sloops were even converted into racing vessels, with certain models gaining fame for their speed. Conversely, slower racing sloops were often refitted as working boats. Over time, the rigging of these vessels evolved—especially after the Civil War. The mast was moved further aft, and the gaff was extended, which improved performance.

Types of New York Sloops

As historian Chapelle notes, Kochiss outlines three primary configurations of the New York sloop, each tailored to meet the needs of the oyster industry:

- The Open Deck Boat: Typically 18 to 25 feet long, these vessels lacked a cabin and featured an open hold amidships for carrying oysters. Often converted into racing boats, these vessels—particularly the sandbaggers—became famous for their exceptional speed.

- Open Boat with Forward Cabin: Similar to the open deck boat but with a cabin located near or aft of the mast. This design was ideal for transporting oysters, as the cabin helped prevent cargo from shifting when the boat heeled over. Slightly larger than open deck boats, these vessels also provided shelter for the crew.

- Deck Boat with Cabin Aft and Hold Forward: The most common type of oyster boat in New York and Great South Bay, these boats typically measured over 30 feet in length. They featured a fully decked hull with a hold amidships, and larger vessels often had a forecastle for crew accommodations. This configuration was highly seaworthy and easy to handle, especially when transporting oysters to market.

Notable Long Island-built vessels include the Ann Gertrude (built in Patchogue in 1851), the J.F. Penny (built in Moriches in 1884), and the Priscilla and Ally Ray (medium south-side boats built in Patchogue between 1887 and 1889). South Side Long Island boat builders, many of English and Dutch descent, gained a reputation for constructing high-quality vessels. Their craftsmanship attracted oystermen from Connecticut, who sought out these well-made boats for their operations.

Key figures in boat design included builders such as Oliver Perry Smith and his son Martenus, Samuel C. Wicks & Son, George Miller, Forrest, Charles, and Filmore Baker, George Bishop, and DeWitt Conklin. Other notable builders included Ottis Palmer of East Moriches, the Post brothers of Bellport, Sam Newey of Brookhaven, and Young of Great River. On the North Shore, builders like the Harts (Pryor, Erastus, and Oliver), Chas G. Sammis of Huntington, William Bedell of Glenwood (later Stratford, CT), and the Bayles of Port Jefferson contributed significantly to the industry.

A notable example of a scallop dredge, the Modesty, was built by Wood and Chute of Greenport, NY. Modeled after a sloop built in Great South Bay called Honest, the Modesty was designed for both oystering and scalloping and remains one of the last two sailing workboats built on Long Island. Modesty and Perscilla were both used to aid shipwrights when restoring Mystic Seaport’s Nellie back to her original sailing build.

As Kochiss mentions, important sailmakers of Long Island, including Charles Miller (whose shop was located above Samuel C. Wicks & Son in Patchogue), worked closely with boat builders. Independent sailmakers like Frank C. Brown of Patchogue and Frank Mills of Greenport also contributed to the success of these vessels. Wm J. Mills and Co. is the oldest sailmaking family in America, and Mystic Seaport Museum holds the family’s collection of historic sail plans dating as early as 1857.

Freight and the Versatility of Coastwise Schooners

Freight carriers, often referred to as “coastwise schooners,” “Long Island Sound freighters,” or simply “runners,” were typically centerboarders known for their remarkable versatility. These vessels had a shallow draft and long, straight keels that allowed them to rest on beaches between tides, making them ideal for loading cargo such as cordwood or sand for foundries, and for repairs.

Many areas around the coast of Long Island and throughout the sound provided incredible challenges due to unique beds, shallow waters, large sandbars, and more, making sailing hazardous. Due to the design of the freight vessels, they provided a safer form of transporting oysters, but at an additional cost.

Innovation in Vessel Design

In addition to traditional vessel designs, some boat builders created specialized craft tailored specifically to the needs of oystermen. These innovations enhanced the efficiency, performance, and comfort of those working the oyster beds. However, oystermen were never content to rely solely on conventional designs. Driven by a constant desire to improve their vessels and harvesting methods, they continually sought new solutions. As a result, fleets of standard boats were often supplemented by more unusual craft—each offering unique advantages to the industry. Among the most inventive were a paddle-wheeler, several power scows, a trimaran, and even a small submarine (Kochiss 1991, 146). These unconventional designs underscore the creativity and resourcefulness of oystermen, who sought to address the ever-evolving challenges of their trade. These unique boats, though unconventional, illustrate the dynamic nature of the oyster industry and the persistent drive for innovation among its practitioners.

The sidewheel dredge boat, designed by Captain Charles S. Mott and built in Patchogue in 1894, is another notable example. Another “novel oyster boat,” a scow called Peconic, was completed in 1907 by Greenport Basin & Construction Co. yards. The vessel, specifically engineered to navigate the narrow Shinnecock Canal while transporting oysters, was built for Fred Lewis, Jacob Ockers, Wm. J. Mills, and Fred Ronik (Kochiss 1991, 147).

The Transition to Powered Vessels

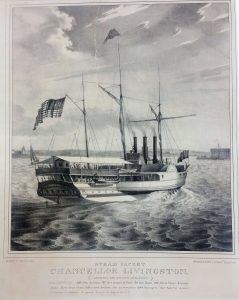

The arrival of steam, gas, and diesel engines in the late 19th century marked a pivotal shift in the oyster harvesting industry. Powered vessels allowed for faster, more efficient harvesting, though many oystermen continued to rely on traditional sailboats for a number of reasons, including state regulations that restricted the use of power vessels when harvesting in bays, rivers, and low areas of water. As steam-powered dredges became more common, larger companies began to design and produce equipment, including dredges, hoisters, and engines to operate them.

In response to the increasing use of steam power, oystermen feared that the new technology would deplete oyster beds, leading to legislation in 1879 that restricted the use of powerboats on natural beds to just one week per year. This law, aimed at preserving oyster stocks, helped maintain the dominance of sailboats for a time. However, by the 1880s, steam-powered boats were fully embraced, and many oystermen transitioned to these new vessels.

Despite initial opposition to steam-powered boats, particularly from oystermen who feared the impact on natural beds, the technology eventually gained widespread acceptance. By the 1880s, steam-powered boats had proven their worth, and oystermen increasingly relied on these vessels for their efficiency. The introduction of gasoline engines further transformed the industry, offering oystermen a more compact, easier-to-maintain alternative to steam.

One notable vessel, the Louis R., built in Stratford, Connecticut for the Andrew Radel Oyster Company, was the last steam-powered oyster boat in the region, finally converting to diesel in 1961.

Gas-powered boats became particularly popular due to their ease of use, requiring no fireman or engineer, and with quick-starting engines. The design of these boats evolved as well, with the addition of an extended house to protect oysters during transport. These boats often retained masts for emergency situations, hoisting sails for power when the engine failed as well as the sails providing stability in bad weather. The introduction of gasoline engines marked a brief but significant period of innovation, leading to a resurgence in demand for wooden boat construction.

However, regulations on natural oyster beds in New York limited the use of powered dredging, and by the early 20th century, wooden shipbuilding had largely faded from southern New England. Iron and steel replaced wood for most vessels, though only a few steel oyster boats were ever built. By the 1930s, the construction of oyster boats in the New York and Connecticut areas had significantly declined. The majority of building took place in Maine.

Tools of the Trade: From Hand Rakes to Modern Machinery

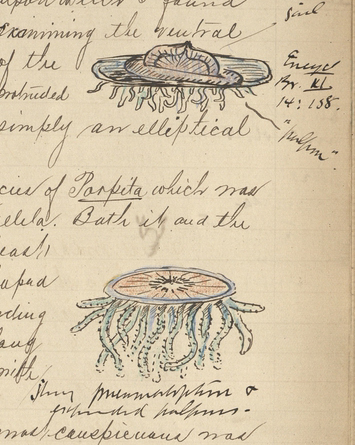

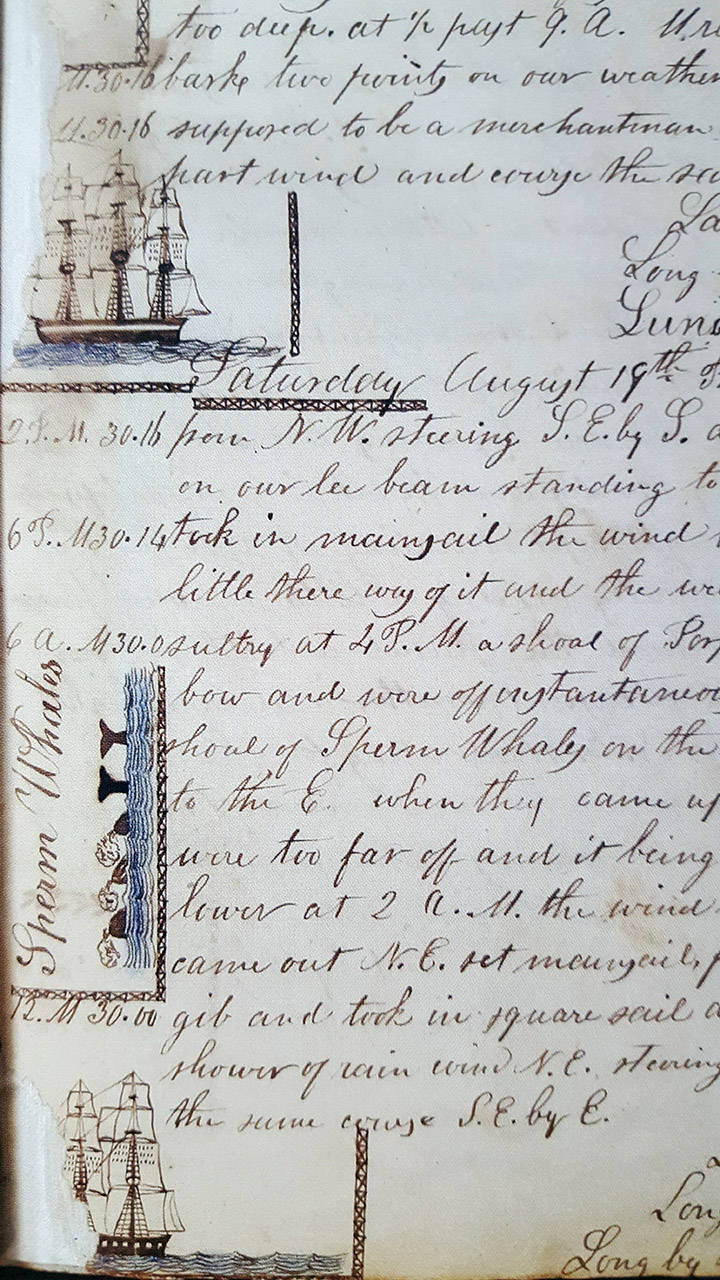

The tools used in oyster harvesting evolved alongside the vessels. Early Indigenous techniques included simple hand-held rakes made from forked sticks, as depicted in a 1585 drawing by John White. By the mid-18th century, more sophisticated rake designs were in use, with long iron teeth bent inward for greater efficiency. These rakes were commonly lashed together in pairs for use by single or double fishermen.

As the 19th century progressed, local blacksmiths began crafting specialized oyster tools, including tongs, which became synonymous with American oystering. These tongs were ideal for shallow waters and were often used on small boats like skiffs, canoes, and sharpies. There were several types of tongs, including scraper, oval, and toothed blades, each suited for different conditions.

The invention of the dredge, which had been used by the Romans and introduced to America by the British, revolutionized the oyster industry. Dredges allowed oystermen to harvest oysters from deeper beds, significantly improving efficiency. By the late 19th century, mechanical dredges, hydraulic booms, and other innovations further modernized the industry.

Modernization and the Future of Oystering

Today, oyster cultivation methods reflect a blend of tradition and innovation. While some oystermen continue to rely on bottom culturing methods—producing oysters with strong shells but leaving them vulnerable to predators—others have embraced off-bottom methods like cage culture, rack-and-bag culture, and suspended culture. These newer techniques offer better protection from predators and more controlled growing environments, though they come with their own set of challenges.

Technological advancements have also reshaped the industry. The introduction of automated sorting machines and tumbler systems has increased the efficiency of sorting oysters by size and controlling shape. These innovations allow oyster producers to meet the commercial demand for consistently shaped oysters, reducing the labor-intensive nature of harvesting and packaging.

However, modern oystering faces new challenges—both environmental and man-made—forcing the oyster industry to continue adapting. Looking ahead, the future of oystering on Long Island remains promising. With a renewed focus on sustainability, efficiency, and technological innovation, the oyster industry is poised to thrive. While the challenges may evolve, the adaptability of oystermen and their continued embrace of new techniques will ensure that the legacy of oystering endures for generations to come.

From its Indigenous roots to its modern technological advancements, oystering on Long Island has evolved significantly over the centuries. The vessels, tools, and methods used by oystermen have continuously adapted to meet the challenges of the times, ensuring that the industry remains a vital part of the region’s culture and economy.